Since the arrangement of the United States under the Constitution, the legislature has adopted different and once in a while disputable strategies to the enlisting of government and state authoritative staff, or the common administration. When all is said in done, the essential decision has had all the earmarks of being between, from one viewpoint, a managerial staff that speaks to and mirrors "the general population" and, on the other, one that is comprised of long haul experts with the learning and experience important to do the intricate and requesting undertakings of government.

Authentic BACKGROUND

Amid the provincial years, it was normal to fill open workplaces with the individuals who paid for them. This experience, alongside aversion of the British frontier administration, gave abundant reason for the pioneers of the new republic to doubt open representatives. Amid his two terms as president, George Washington demanded "wellness of character" as the prime capability to hold an administration work. This standard, it was trusted, would make a "patrician" common administration that would keep away from what numerous saw as the traps of majority rule government. Expulsions from office were uncommon.

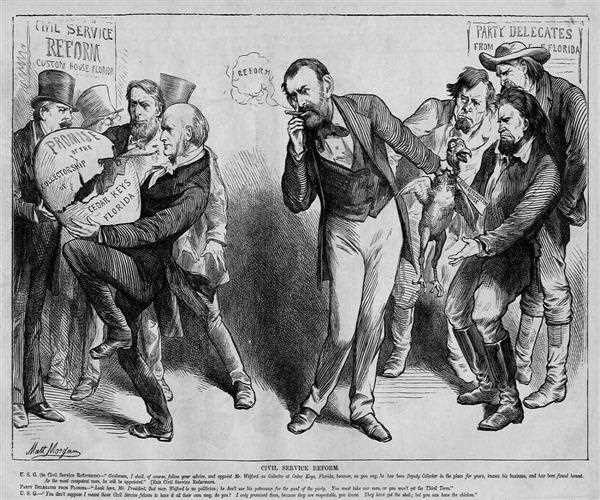

THE CALL FOR CIVIL SERVICE REFORM

Following the Civil War, the development for common administration change increased. People in general was scrutinizing the corruption on moral grounds. Also, numerous lawmakers had come to trust that the undeniably convoluted mechanical economy required an abnormal state of information and experience among common administration workers. Such capabilities were fundamental for open approach to be satisfactorily figured and executed.

It took the death of President James Garfield in 1881 by a crazed baffled office-searcher to make change a matter of the most elevated desperation. Amusingly, the VP who turned into the following president, Chester A. Arthur, had himself been a firm adherent to and recipient of the corruption. Be that as it may, to the astonishment of his previous political partners, Arthur, trusting that his re-election would rely upon connecting with more reformist and free components in the electorate, advocated the order of common administration change.

THE PENDLETON ACT AND RELATED ACTS

The well-known inclination against political support was running so solid that the two Democrats and Republicans united to sanction the principal Civil Service Act, known as the Pendleton Act (22 Stat. 403), in 1883. This demonstration, to a great extent drafted by the New York Civil Service Reform Association, made the Civil Service Commission, which was coordinated to make an arrangement of aggressive examinations to fill an opening in government benefit positions and to guarantee that the common administration was not utilized for political purposes.

Initially, just around 10 percent of government positions were incorporated inside what was known as the "grouped" administration, yet that rate developed to more than 70 percent by 1919.

THE CIVIL SERVICE REFORM ACT

By the 1970s disappointment with the activity of the common administration framework had turned out to be widespread to the point that lawmakers knew they needed to make a move. Procedural assurances for workers were seen as deficient. Numerous condemned the Civil Service Commission for neglecting to ensure representatives' rights, especially when charges of racial, sexual, and different sorts of segregation were made in light of proposed workforce activities.

As associations developed among the government workforce, elected representatives and others voiced worries that no free fair-minded organization existed to administer the elected division's work administration program. These faultfinders likewise observed a need to reinforce the part of the framework for settling a debate that included unionized workers and their utilizing organizations.