Sometimes, routes of the Underground Railroad were organized by abolitionists, people who opposed slavery. More often, the network was a series of small, individual actions to help fugitive slaves. Stations were added or removed from the Underground Railroad as ownership of the house changed. If a new owner supported slavery, or if the site was discovered to be a station, passengers and conductors were forced to find a new station.

Using the terminology of the railroad, those who went south to find slaves seeking freedom were called “pilots.” Those who guided slaves to safety and freedom were “conductors.” The slaves were “passengers.” People’s homes or businesses, where fugitive passengers and conductors could safely hide, were “stations.”

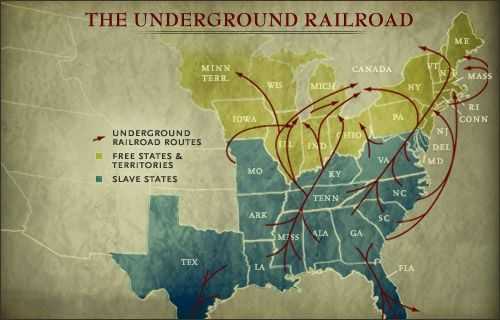

People sympathetic to their cause, such as abolitionists or other freed slaves, would aid them in escaping and getting to safety. An estimated 100,000 slaves escaped to freedom using the Underground Railroad from 1810-1850, though it was used most in the 1850s and 60s. Ontario, which was a part of British North America, was perhaps the most popular destination for escaped slaves, as all slavery was prohibited. The exact numbers are unknown, but at least 30,000 escaped slaves were able to escape to Canada where all slavery was illegal. Perhaps more than 100,000 people were able to though.