For quite a while, Americans thought they knew the responses to these inquiries. Educated fundamentally by the agrarian vision of scholars like Thomas Jefferson, Americans valorized a country of little, free ranchers and specialists.

Riches were suspect: it produced bad habit and it tainted individuals and countries. Rivalry was esteemed as a wellspring of development and proficiency. Moreover, the dedicated little makers of this financial vision were thought to make perfect subjects. Uncorrupted by riches, and rendered impenetrable to political weight by their financial independence, they were capable, objectively and idealistically, to perceive and advance the collective premium that should lie at the focal point of open approach. Citizenship and patriotism were compared with benevolence, the subordination of self-enthusiasm to more prominent's benefit of the country.

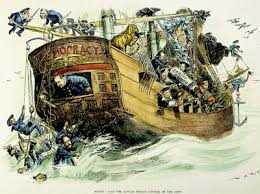

However, amid the Gilded Age, this vision was tested. The tremendous changes in the American economy constrained a reevaluation of these long-held, however maybe out of date esteems. The development of substantially bigger business undertakings, the age of significantly more prominent individual fortunes, and the surfacing of another kind of government official constrained Americans to rethink the qualities characterizing American culture and legislative issues.

The test to conventional American standards started with the sheer size of America's new ventures. In 1900, Andrew Carnegie worked eight steel processes and delivered in excess of 4 million tons of steel annually.39

John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil worked many refineries, controlled approximately 90% of the country's oil, and produced $57 million in benefits in 1904.40

How did a modern domain like Carnegie's fit into the old republican vision? How could Rockefeller's imposing business model on oil refining, worked by driving his rivals bankrupt, be squared with the old republican vision of a country of little makers?

One answer was given by Social Darwinism. Social scholars like William Sumner and Herbert Spencer connected Charles Darwin's speculations of regular choice to the economy and contended that the ascendance of these modern monsters was "normal." Competition was nature's method for accomplishing progress. Now and again the procedure could be brutal: there were inescapable setbacks. Yet, rivalry guaranteed that humankind walked separately and by and large toward a superior future.

"Cheers"