Amid the mid-1800s, the United States needed terrains that Native American gatherings possessed east of the Mississippi River. The youthful country required land for proceeded with extension. Possessing the district alongside Native Americans was not a genuine thought since white pilgrims had faith in private land proprietorship that stood out obviously from the Native American idea of common property.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was the Congressional answer for the predicament. This law moved Native American clans to areas west of the Mississippi and gave the president the expert to arrange settlements to execute expulsion.

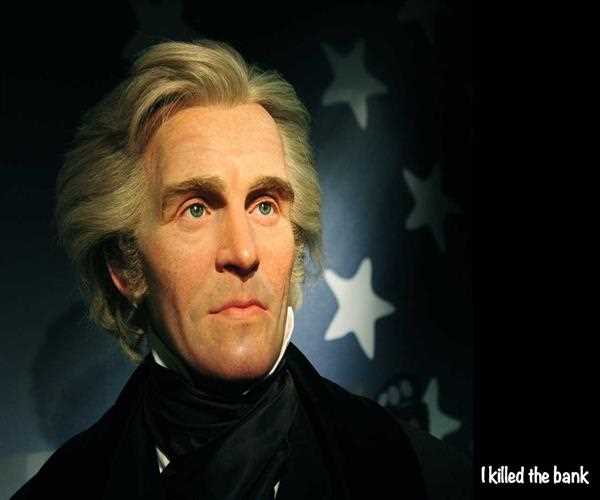

After Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, President Andrew Jackson marked it into law on May 28, 1830. The president had a past filled with hostility with Native Americans. Jackson, filling in as an armed force officer, vanquished the Creek Nation in 1814. Thus, the United States assumed control 20 million sections of land in an area from the Creek. Throughout the following decade, Jackson constrained Native American gatherings to surrender arrive all through the Southeast. Out of the 11 arrangements Native Americans marked in the vicinity of 1814 and 1824 surrendering area to the United States, Jackson assumed a focal part in nine.

Actualizing the Removal Act

President Jackson campaigned Congress to draft a law furnishing him with the ability to give western terrains to Native Americans. As a byproduct of the land gives, the clans would need to surrender all cases to lands east of the Mississippi River. Subsequently, 50,000 individuals moved to supposed Indian Territory in introducing day Oklahoma under arrangements marked with Jackson.

The Removal Act legitimized Jackson's longing to take Native American terrains. Things worked easily in such manner when clans acknowledged the terms Jackson set out for them, however, the unfaltering Cherokee declined to submit and stayed in Georgia. Undermined with expulsion under state law, the Cherokee documented suit in the United States Supreme Court.

On account of Worcester versus Georgia (1832), the judges decided that the Cherokee were an autonomous country living inside the outskirts of the United States. The State of Georgia couldn't persuasively expel the Native Americans west, the choice proclaimed. Andrew Jackson declined to back the decision, leaving the Cherokee unprotected against Georgians resolved to settle the land.

Trail of Tears

Symbolic of expulsion strategy was a definitive destiny of the Eastern Cherokee. The Jackson organization overlooked the Supreme Court managing and marked the Treaty of New Echota with a little gathering of Cherokee in 1835. This minority moved to Oklahoma. Most of the clan stayed in Georgia, referring to their rights under the prior Supreme Court administering.

President Martin van Buren, who succeeded Jackson, sent government troops to Georgia in 1838 to lead a constrained walk to Oklahoma. On November 12, 1838, around 12,000 Cherokee started the 800-mile travel from Georgia. Appraisals are that 4,000 kicked the bucket en route.